Australia and space

Australia’s space sovereignty

Delivery of space-enabled services depends on reliable and continued access to satellite systems and their data streams. With some minor exceptions Australia does not have a history of ownership of satellites and systems.

Instead, the national focus has been on exploitation of the systems of other nations or organisations through a globally well-regarded approach to collaboration.

Characterised by a multi-source approach, Australia has developed applications that integrate different types of data from different suppliers and partners with the benefit that:

- the applications are richer (e.g. by exploiting the strengths of different systems in a complementary manner, or using multiple systems to provide additional data to increase spatial and temporal coverage); and

- Australia is more insulated from technical failures (e.g. instrument failure) or sudden changes in the policy environment (e.g. sudden changes to data policy).

Australia is likely to continue to build on this approach to enable the delivery of better products to users and consumers locally, and globally. Moreover, Australia’s openness to using what is available is not just of interest to Australia, but also to the approximately 170 or so other nations who would prefer not to be dependent on data controlled by a single major supplier. Continued encouragement of the multi-source approach positions Australia well to export space-enabled services.

However, Australia must also consider how to better manage the risks associated with dependence on other nations and foreign companies. Continued and increased investment in ground segment partnerships will continue to be a key part of generating goodwill. Australia is keen to continue to encourage global coordination of satellite systems, the use of standards and ‘open public data’. This approach has given Australia access to a richer diversity of data types than would be available under an uncoordinated approach with every nation focussed only on unilateral outcomes.

Australia’s space industry could, however, play an important role in developing niche capabilities and systems that address key risks and opportunities. This capability should be developed, and then leveraged, to address scenarios where Australia:

- has something of value to contribute to the space segment of critical partner programs (in return for assurance of future data supply).

- has unique local or regional needs, that are highly unlikely to be met internationally.

- can support users to strengthen the ‘multi-source’ approach, for example by providing cross-calibration of foreign missions.

- can make contributions to the global observing system, and thereby encourage ongoing coordination and data sharing by others.

- can identify risks where sovereign access or control can reduce our exposure to an acceptable level.

- can obtain timely access to data, as one component of assurance, that contributes to high priority national needs

Developing and nurturing our nascent space industry’s capabilities to meet these needs in any operational (as opposed to experimental) sense will take time. It will need support and encouragement from government, including to ensure our industry has the necessary maturity and technical readiness. Australia has highly trained people, and many innovative businesses.

However, many of the satellite systems Australia relies upon for the data that underpins spatial services are highly sophisticated with a proven record for operational reliability.

Although changes in satellite technology do lower barriers and create new opportunities, a clear-eyed approach, responding to requirements and drivers in the market, will be needed when considering the development of national missions.

Defining Australian Space and Spatial Sovereignty

There has been increasing use of the term sovereignty and concern about supply chain vulnerability in relation to the space sector by Government in recent times. Major legislative and policy announcements such as the Security Legislation Amendment (Critical Infrastructure) bill, the Modern Manufacturing initiative and the Defence Strategic Update all make reference to a need for sovereignty and reduced reliance on global supply chains for critical infrastructure, systems and technology including space.

It would be useful to derive an agreed definition of ‘sovereignty and the national need’ in the context of access to Australian space and spatial services.

A working definition of sovereignty and the national interest would address the required degree to which Australia is capable of determining and prosecuting actions deemed by Government to be in our national interest; free of interference, coercion or limits imposed by other nations.

This might include access to, and the operation of, the space systems themselves, or to intellectual property allowing effective operation of the system in question.

Sovereignty and the national need might be implied to infer requirements for ownership and /or control from Australian legal entities or from within Australian geography. Within the space and spatial sector, this could extend to the industrial capability that supplies goods and services and ownership/control of supply chains upon which acquisition, operation and sustainment of all components of the enterprise depend, and the skillsets and capability in the workforce, the research sector and the public service.

Interference, coercion and limits might result in constraints on what space services Australia can access. It may also be observed as degradation of available services if Australia’s interests do not align with the interest of the supplying organisation or their host nation.

For example, an imagery provider may not support request for data over certain geographic areas or a government operator of a GNSS system may degrade or turn off a timing signal for a certain time or over a certain geographic area. A communications service provider may not, or may not be able to, provide coverage or limit available RF bandwidth at certain times or over certain locations.

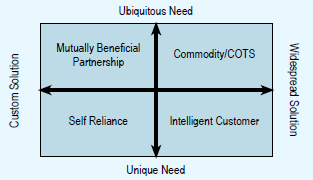

The following diagram shows how procurement strategies might recognise when such controls could hinder our freedom of action and drive the need for national self-reliance or sovereignty.

Commodity/COTS – if a service is truly available from multiple independent sources it might be possible to achieve sovereignty without any self-reliance. But if the market changes, and in the space sector it can change with little notice, the Government must be prepared to move quickly to create alternate sources to support critical services.

Intelligent Customer – a term used by the UK Ministry of Defence would mean that Australia maintains the ability to define our needs and specify a capability solution, including oversight to ensure effective contractual delivery even if the goods/services are sourced entirely from overseas. An intelligent customer also takes a hands on approach to operations and sustainment (including upgrades) throughout the life of a capability. Optus is a prime example of an Australian space service intelligent customer and acted on behalf of Defence in this role during the acquisition of the Defence Payload System on Optus C1.

Mutually Beneficial Partnership – Describes an approach where no one country or organisation has the ability to develop, deliver, operate and sustain a capability so creates a partnership to do so. This only delivers sovereignty if partners have strongly aligned interests in the development and operation of the capability and a degree of mutual inter-dependence can be achieved. JSF is an example of this model as is the Wideband Global SATCOM MoU which had a number of specific provisions to enhance Australian sovereignty within this partnership.

Self Reliance – describes acquisition and sustainment of a capability where Australia controls/directs a significant portion of the value-chain. Critical components of the capability are sourced from Australian suppliers. It is impossible to attain full self-reliance due to the globalised nature of supply chains, especially for electronics which is a crucial component of almost every Australian space capability. The best example of self-reliance is JORN and arguably the Collins Class has forced Australia into self-reliance during the sustainment of that capability.

It is possible that self-reliance may deliver a lower level of capability unless Australia is prepared to support (and this may mean significant financial support) a high level of industry capability across the space value chain, especially R&D. This is because the financial base of Australia may not support the same level of research, development and innovation as larger North American or European manufacturers. Evidence for this can be found in previously published research from the UK that showed a strong correlation between national R&D funding and defence equipment capability levels.

This issue is identified within the 2020 Defence S&T Strategy which states:

“There are some Defence capabilities that must be developed domestically, because overseas sources may not provide the assurances we need or the capability requirement might be unique to Australia. Through the 2018 Defence Industrial Capability Plan, the government is committed to growing Australia’s ability to operate, sustain and upgrade Defence capabilities with the maximum degree of national sovereignty. A well connected, informed and vibrant defence S&T enterprise will be critical to this objective.”

Based on this and the complexity of supply chains contributing to space-based capabilities that provide communications, PNT, imaging and other forms of sensing it is difficult to determine which elements of a system need to be produced or operated from within Australia as the needs may change over time.

Space and spatial service rely as much on ground-based infrastructure as space-based assets. Ground infrastructure located within Australia may still be subject to international agreements which can place constraints on Australian usage inhibiting access despite being located on Australian territory.

For space systems, assured access (including the ability for timely tasking and commanding of a spacecraft) may achieve the same outcome as sovereign ownership or control. A viable pathway to assured access may be through partnership whereby a two or more nations pool resources to deliver a system with contributors gaining

guaranteed access to the joint system. This may include provision of ground infrastructure in a suitable geographic location for critical facilities along with dependable undertakings by owners that these facilities will be maintained, including through access to expert staff, to ensure an agreed level of assurance that services will be available when and where needed.

Under this collaborative partnership model, which is quite common in the space sector, a more nuanced approach to both critical infrastructure protection and sovereignty may be required to ensure the desired outcome of service availability for Australia customers are met.

Risks arising from non-sovereign ownership and control of assets may also mitigated through the underlying technology employed by the system. For example, modern GNSS receivers can access signals from multiple systems meaning customers do not rely on any single provider (note there are six Global and Regional Navigation Systems that operate over Australia). If one operator disables or denies access to their system, users can still access a viable service. Such inter-dependencies and alternatives need to fully understood when determining appropriate approaches to ensure assured access to space and spatial services.